Kimono Virtual Exhibit

Virtual Exhibit: History of Kimono through Art

This project focuses on examining how changes in kimono fashions and artistic representations connect to larger historical trends such as ideas of femininity, ethnic identity, and tradition vs modernity. While kimono has historically been worn by everyone in Japan, this project focuses specifically on kimono that wealthy, elite women have worn throughout history. This decision was made due to space constraints; it would not have been feasible to cover all styles of kimono in a single timeline. This online exhibit is curated by 2022-2023 Carolina Asia Center Public Humanities Fellow Sophie Eichelberger.

Kimono is a garment that dates back to the Heian period (794-1185). Until Japan modernized in the nineteenth century, everyone in Japan wore kimono every day. Early iterations of the kimono have the general T-shape that today’s kimono does, but the way of wearing the garment as well as patterns and construction has changed drastically from the Kofun-Nara period (300 CE-794 CE) to today. In contemporary times, kimono is very closely associated with traditional Japanese culture and is worn primarily by women at cultural events, such as the tea ceremony. How did the way of wearing kimono change so much? How does the garment represent gendered identity differently today than 300 years ago? The interactive timeline below traces how larger shifts in ideas about gender, class, and ethnic identity are represented in when, how, and why kimono has been worn.

Interactive Timeline

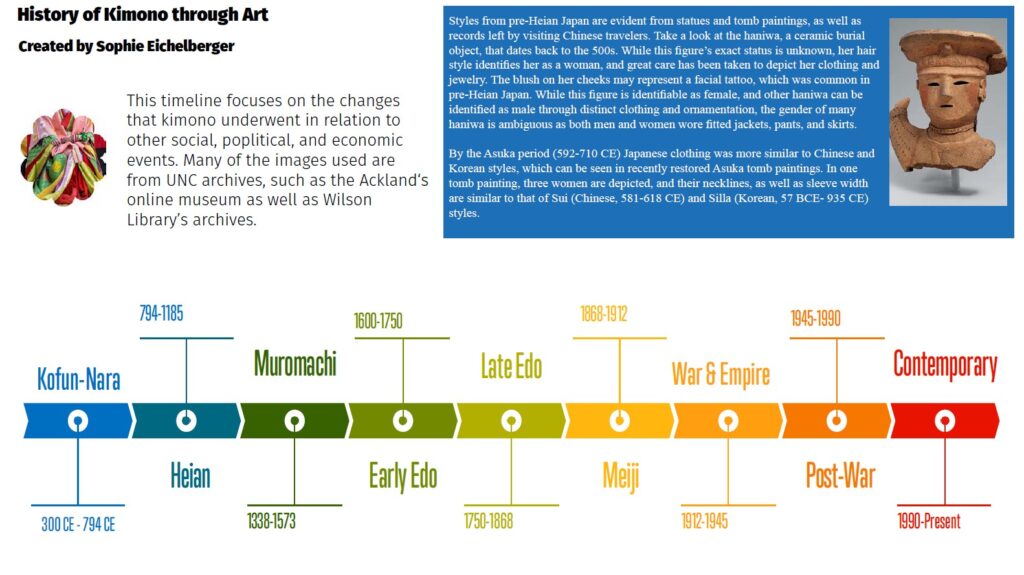

Please click here to view the interactive timeline entitled History of Kimono through Art. This timeline is divided into nine different eras: Kofun-Nara, Heian, Muromachi, Early Edo, Late Edo, Meiji, War & Empire, Post-war, and Contemporary. If you mouse over the name of each period, a pop-up box will open in the top-right corner with information about dress in the period. As each box is not particularly large, only a brief overview of each period is included, and there are many details about the history of kimono that are not included in this timeline. For more information, check out the additional links below. Please note that the image below is an image of the timeline, and is not interactive.

To download the timeline as an interactive pdf, please click this link: Kimono Interactive Timeline

Kofun-Nara (300 CE – 794 CE)

Styles from pre-Heian Japan are evident from statues and tomb paintings, as well as records left by visiting Chinese travelers. Take a look at the haniwa, a ceramic burial object, that dates back to the 500s. While this figure’s exact status is unknown, her hair style identifies her as a woman, and great care has been taken to depict her clothing and jewelry. The blush on her cheeks may represent a facial tattoo, which was common in pre-Heian Japan. While this figure is identifiable as female, and other haniwa can be identified as male through distinct clothing and ornamentation, the gender of many haniwa is ambiguous as both men and women wore fitted jackets, pants, and skirts. By the Asuka period (592-710 CE) Japanese clothing was more similar to Chinese and Korean styles, which can be seen in recently restored Asuka tomb paintings. In one tomb painting, three women are depicted, and their necklines, as well as sleeve width are similar to that of Sui (Chinese, 581-618 CE) and Silla (Korean, 57 BCE- 935 CE) styles.

Heian (794-1185)

Japanese style is often traced back only as far as the Heian period because this was when elite, court women’s clothing developed into a complex fashion stystem. What we refer to today as “kimono” was developed in the Heian period, but at the time, it was considered women’s underwear. When women got dressed during the Heian period, they first donned a white, short kimono, and pants known as hakama. Then, on top of that, women layered up to twenty garments in a style known as “junihitoe.” Clothing was an important signifier of someone’s age, class, gender, and marital status, and it was only elite women who could wear junihitoe, as it was incredibly expensive and heavy. The beauty of the junihitoe came from the layering of colors, and certain colors could only be worn during

certain times of the year, and some were forbidden entirely.

Muromachi (1338-1573)

In the early Muromachi period, it was common for women to wear hakama, wide-legged trousers, without an overskirt (which had been present in the Heian period). However, by the end of the Muromachi period, hakama disappeared from daily wear, and the “kosode,” or “short-sleeve” underwear from the Heian period developed into outerwear. During this period, obi, or the broad sash of today’s kimono, was developed, though it was much more narrow than it is now. Like the Heian era, women wore many layers, though a new invention was to drape an additional kosode on one’s head, somewhat like a cape. As for the fabric that kosode and obi were constructed from, richly embroidered Chinese-style textiles were popular during the Muromachi period. The fabric pictured on the right is a small detail of a kosode made of Chinese-style textiles that dates back to the Muromachi period.

Early Edo (1574-1750)

Kimono fashions during the early Edo period were set by women of the licensed sex-work quarters as well as kabuki actors who performed as women on-stage. A time of relative peace, the early Edo period was prosperous, and women often wore gold embroidery, expensive silks, and imported fabrics such as velvet to highlight their wealth and popularity. The height of exorbitant early Edo fashion was during the Genroku period (1688-1704). Towards the end of the Genroku period, the government instituted sumptuary laws in an attempt to control the extravagent fashions of sex-workers and other lower-status individuals. After the Genroku period, fashions changed towards a more subtle aesthetic, though it is unknown whether that was due to sumptuary laws or if influential sex-workers and kabuki actors made the switch towards a more subtle aesthetic themselves. Kimono shape continued to change throughout the early Edo period; sleeves grew significantly in length, obi were widened to accommodate the proportions of the longer sleeves, and skirts became longer.

Late Edo (1750-1868)

By the 1750s, color woodblock prints mass-produced, and images of fashionable styles were readily accessible. The new woodblock technology allowed for a booming fashion industry that was intimately connected to print culture. Fashion leaders (such as geisha), woodblock printers, and textile producers were all connected and reliant on each other to create a flourishing fashion culture that was based in large urban centers and could spread to rural areas. Geisha were on the forefront of fashionable developments. Unlike the sex-workers/courtesans of the early Edo period, geisha were not inherently involved in sex-work; they were entertainers who trained in music, dance, and conversation. Like courtesans, though, geisha were trendsetters in the late Edo period, and popularized additional hair pieces and longer hem lengths for kimono. Additionally, the late Edo period saw an increase of European influence on fashion, and one Nagasaki geisha made waves by wearing “Western frock and crinoline” as early as the 1860s.

Meiji (1868-1912)

The Meiji era is remarkable for the drastic increase in contact with foreigners, specifically Europeans and Americans. Japan began to modernize, or adapt Western ideologies about government and social life. Clothing also changed drastically. In images from early in Emperor Meiji’s reign, the Emperor wears Western suits, and the Empress European ball gowns. On January 17, 1887, the government released an imperial proclamation that encouraged women to adopt Western modes of dress; women had previously resisted the switch to Western fashions, possibly because it consisted of voluminous skirts and restricting corsets. According to a Japanese magazine, in 1890 “except for a few ladies of the nobility, hardly any women are wearing Western clothes this year.” In day-to-day life, despite the sweeping changes to the Japanese government, for the average Japanese woman, kimono remained the daily garment of choice.

War & Empire (1912-1945)

Part of the modernization that began in the Meiji era was increased militarization, which continued through the 1940s. During this period, Imperial Japan engaged in multiple wars, and men and women’s kimono from this time reflects the tools of the expanding empire. The kimono on the right, for example, is a woman’s kimono which is decorated with plane motifs. While quite a few new kimono were produced and worn during the 1920s and 1930s, by the early 1940s kimono became a symbol of luxury, and were deemed wasteful and unpatriotic. During the Pacific War (1941-1945) many kimono factories shut down, and fabrics were rationed until 1951. Due to the silk shortage during the war, many kimono were repurposed into military uniforms. It was during this period that kimono began to fall out of favor, and in the post-war period its status as traditional and ceremonial garb was cemented.

Post-war (1945-1990)

After the Pacific War, American military occupation (1945-1952) of Japan greatly influenced the role of kimono in Japanese women’s fashion. During this period, trends from Europe and America became fashionable in Japan, as well. An example of this is the “preppy” style, which paid homage to the styles worn at American Ivy League universities, such as sweaters, polos, and khakis (pictured on the right). Kimono began to be reserved mostly for women, and also for practices linked with Japanese culture such as the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, or upscale sushi restaurants. Other instances when kimono continued to be worn by women were at special events, such as visits to shrines, the coming-of-age ceremony (seijinshiki), and university graduations. In the post-war period, kimono came to represnt “traditional” Japan, and was directly juxtaposed with “modern” Japan.

Contemporary (1990-Present)

Through the 1980s, the Japanese economy recovered from the devastation of the Pacific War until it was the second strongest economy in the world. In the 1990s the bubble burst, and as the economy changed, so did kimono buying habits. Women could no longer afford expensive, ceremonial kimono, and instead turned to second-hand kimono shops. Since the 1990s, kimono has been incorporated into Japanese street fashion, where it is worn in non-traditional ways. Combining kimono with jeans, or bright-colored hair is a way through which Japanese individuals can re-interpret their national identity. Social media allows for kimono’s current fashionability, as people in places such as Japan, the Netherlands, and America can all discuss ways of styling kimono. While it has risen in popularity in street-fashion,women continue to wear high-end kimono to events such as the tea ceremony. Fashion magazines are important in this arena, and magazines such as Utsukushii Kimono (Beautiful Kimono) continue to reify current definitions of what proper Japanese kimono should represent.

Additional Information

For more information about the history and evolution of kimono, check out these resources!

Digital links

For more about the haniwa pictured in the timeline, click here

To learn more about haniwa in general, click here

For more about the recently-restored Asuka period paintings, click here

For more about the influence of Chang-An culture in Japan, click here

For more about pre-modern Korean clothing, click here

For more about Heian era clothing, click here

For an overview of clothing from different Japanese eras, click here

For more about karaori, click here

For a detailed image and information about a kosode, click here

For more about book publishing and fashion in the Edo period, click here

For a brief overview of the history of kimono, click here

For more images of Japanese street culture from the 1980s forward, click here

Books and articles

Dalby, Liza Crihfield. Fashioning Kimono: Fashioning Culture. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001.

Jackson, Anna. Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk. London: V&A Publishing, 2020.

Milhaupt, Terry Satsuki. Kimono : A Modern History. London: Reaktion Books, Limited, 2014. Accessed November 2, 2021. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Swinton, Elizabeth de Sabato, Kazue Edamatsu Campbell, Liza Crihfield Dalby, and Mark Oshima. The Women of the Pleasure Quarter: Japanese Paintings and Prints of the Floating World. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1995.