How Dr. Frank Came to Serve on the UN Committee of Good Offices

This page is the fourth of nine in a virtual exhibition on Frank Porter Graham’s role in negotiations for the recognition of Indonesian independence. See the homepage for the exhibition here. See the previous page here. See the next page here.

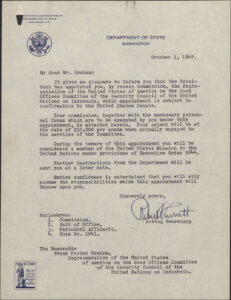

After the UN had set up the Committee of Good Offices and the United States of America had been appointed as a member—in fact, as the chair, because it was the choice of the other two member states—the US government needed to find a capable man to serve in this unprecedented role. The Truman administration turned to Dr. Frank Porter Graham, appointing him on October 1, 1947, with an annual salary of $12,000 (when actually engaged with the work of the committee).

The press release from the White House announcing Dr. Frank’s appointment did not given a specific reason why he was chosen, but did cite his prior service at UNC, on the National Consumers Advisory Board, National Advisory Council on Social Security, President’s Committee on Education, and the National War Labor Board. It pointedly did not mention his work on civil rights and race relations in a fractured American South, nor the fact that he had no experience at all with Asia, and very little with international affairs. His appointment may have reflected how thinly stretched the US Department of State was at this time, re-establishing embassies around the world and staffing up offices at the new United Nations Organization, or it may have been a sign of the low priority the US government placed on this case. The Dutch had expected someone of much higher stature for this task—and perhaps someone inclined to their side, like Gen. Dwight Eisenhower (who had served with many European commanders in two world wars).[1] In a later statement on the situation, Dr. Frank said he and his colleagues were “condemned by both extremes”:

The members of the first Committee of Good Offices, which included Mr. Justice Richard C. Kirby, of Australia; Dr. Paul van Zeeland, of Belgium; and myself, as the American representative, were accused by some of the Dutch imperialists of being in league with the Republic of Indonesia against the Kingdom of the Netherlands. At the same time I was repeatedly accused by the Moscow radio of being a tool of American capitalism and of intimidating the Republicans into accepting the Renville agreement with threats of atomic bombs and American power.[2]

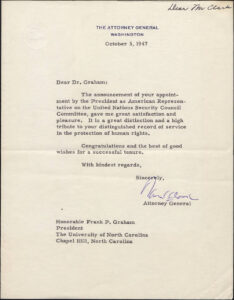

In any case, Dr. Frank’s appointment turned out very positively for the Indonesian cause, and it disappointed Dutch hopes for continued American favoritism (based, at least in part, in the residual racism among American staff on the ground and in Washington). In the US, it seems that the appointment was received quite positively. The Frank Porter Graham collection includes personal letters of congratulation from the Acting Secretary of State (Robert Lovett), the US Attorney General (Tom C. Clark), a special assistant to the president (John R. Steelman), and the American Committee for Indonesian Independence.

An American foreign service officer who later served in Indonesia described Dr. Frank in this way:

A soft-spoken man of small stature, Graham was among the few Americans at the eye level and within the decibel range of Indonesian leaders. His interest in hearing the Indonesian story and his impartiality would earn him greater respect among Indonesians than any previous American visitor to the archipelago.[3]

Appointed in September, Dr. Frank packed his bags and flew to Australia to meet the other two members of the committee in October 1947. Based on his own letters home to his wife, it is clear that Dr. Frank held his colleagues on the committee in high esteem:

Judge Kirby of Australia and Dr. van Zeeland of Belgium are both high-calibred and cordially charming in their different ways. … Dr. van Zeeland, former Prime Minister of Belgium and head of many commissions before, during, and since is quite French in manner and spirit. … Mr. Justice Kirby has an able delegation. … The United Nations has provided an especially capable secretariat.[4]

When he arrived in Indonesia, he wrote to his wife Marion about his respect for the Indonesians when arriving in the archipelago: “We knew we are now on the island of an ancient people, now in bitter strife.”[5] Dr. Frank quickly established rapport with the leaders of the Republic of Indonesia, including the top officials in the government and the negotiating team for the Indonesian side. The assistant to the American delegation, Charles Ogburn, had a much more difficult relationship with Dr. Frank, whom he believed to be out of his depth.[6]

[1] Frances Gouda and Thijs Brocades Zaalberg, American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism 1920-1949 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2002), 223.

[2] Statement of Sen. Frank Porter Graham on Indonesia, from the Congressional Record of April 5, 1949 (81st Congress, Senate, 95, vol. 3, pp. 3839-3849). Read the full statement on the Carolina Asia Center website here.

[3] Paul F. Gardner, Shared Hopes, Separate Fears: Fifty Years of U.S.-Indonesia Relations (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997), 45.

[4] Letter from Frank Porter Graham to Marion Graham, October 27, 1947, in the Frank Porter Graham Papers, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill, folder 1982. Cf. Letter from Frank Porter Graham to Paul van Zeeland, May 16, 1949, in the Frank Porter Graham Papers, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill, folder 2156b.

[5] Letter from Frank Porter Graham to Marion Graham, November 2, 1947, in the Frank Porter Graham Papers, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill, folder 1982.

[6] Gouda and Zaalberg, 224.

Further Reading:

An account that is generally positive on the American role—including the particular contribution of Dr. Frank—can be found in Paul F. Gardner, Shared Hopes, Separate Fears: Fifty Years of US-Indonesia Relations. On the other hand, great insights into the skeptical reactions to Dr. Frank’s appointment can be found in Frances Gouda and Thijs Brocades Zaalberg, American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism 1920-1949, especially chapter 9.

This episode in Dr. Frank’s life is also covered in the many biographies of his life; see these listed among the further reading in the first page of this virtual exhibit.