Indonesia in the 1940s

This page is the second of nine in a virtual exhibition on Frank Porter Graham’s role in negotiations for the recognition of Indonesian independence. See the homepage for the exhibition here. See the previous page here. See the next page here.

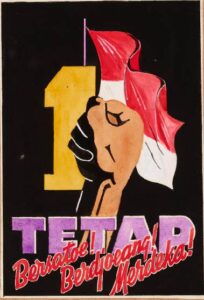

Indonesia is an archipelago stretching from Sumatra in the west to half of the island of Papua in the east, encompassing more than ten thousand islands and hundreds of local languages. Many European nations including the Netherlands had established trading posts in the archipelago since the sixteenth century, seeking unique spices that grew only in certain parts of the so-called “Spice Islands” (today’s Maluku province). From the early nineteenth century, the Dutch began to consolidate the whole archipelago as a direct colony, a process that was complete by 1911. In the first decades of the 20th century, Indonesians increasingly united across ethnic divides and sought self-governance, with a major turning point in 1928 when a student pledge declared “One Nation, One People, One Language” as a guiding mantra for building an independent Indonesia. In the Second World War, the Japanese invaded in 1942 and overthrew Dutch rule quickly and completely, leading to three years of famine, authoritarianism, and deprivation under a wartime occupation.

At the end of the war, Indonesia’s nationalist leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta proclaimed Indonesia’s independence on August 17, 1945. As the former colonial power, the Dutch rejected this declaration, and they (with European Allies) re-invaded Indonesia in an attempt to re-establish colonial control. Indonesia fought for its independence from 1945 until 1949 in a conflict known today as the Indonesian Revolution.

The Indonesian Revolution was characterized on the ground by local militias engaged in guerilla tactics against Dutch forces (and, at the beginning of the conflict, other Allied forces that came in to accept the Japanese surrender). The struggle across the many different islands was chaotic and difficult, including not only violence against the colonizers and their perceived allies, but also clashes between pro-independence groups with different visions for the country’s future (for example, between Communists and devoutly Muslim forces). At the elite level, one major debate was about whether Indonesia should engage in formal diplomacy to achieve recognition as a country or attempt to win its freedom on the battlefield (the latter position was sometimes called “100% Merdeka” or “100% Independence”).

Further reading:

The classic account of the Indonesian revolution is George McT. Kahin’s Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia, written by an American political scientist who was on the ground during the conflict. In recent years, there has been a wave of new historiography about the Indonesian revolution, in recognition of the 75th anniversary, including many great volumes in Indonesian, English, and Dutch from the project Independence, Decolonization, Violence and War in Indonesia, 1945-1950 in the Netherlands.

Because this was a seminal moment in the history of modern Indonesia, scholars have delved into various aspects of the conflict and society at that time. These include the role of women, in Mary Margaret Steedly’s Rifle Reports, the place of organized labor, in Jafar Suryomenggolo’s Organising under the Revolution, or the Islamic vision of the struggle, in Kevin W. Fogg’s Indonesia’s Islamic Revolution—just to name a few.